I was seven going on eight years old when World War II broke out and the Japanese military occupied the Philippines. In 1941, while I was a student at the Cubao Elementary School in Quezon City, I met and was befriended by an officer of the Japanese Imperial Army who was stationed at a post near Camp Murphy in Quezon City, north of Manila.

I was seven going on eight years old when World War II broke out and the Japanese military occupied the Philippines. In 1941, while I was a student at the Cubao Elementary School in Quezon City, I met and was befriended by an officer of the Japanese Imperial Army who was stationed at a post near Camp Murphy in Quezon City, north of Manila.

My dad – an American citizen and US Army veteran – was in hiding at a farm in Cubao that was owned by my sister Rosalia (Rosie) and her husband, Joseph. My dad declined to report to a concentration camp for American citizens at the University of Santo Tomas in Manila as he was instructed by the US Embassy. My dad believed that the war would last “just a few days . . . maybe a month at most.”

My dad – with my stepmother Antonina and me in tow – made the long trip from our home in Baclaran, Parañaque (south of Manila) to Cubao (north of Manila) where my dad believed he would be safe for the “duration” of the war. My younger siblings – Hattie, Thomas, Roscoe, and Emma – were sent to the town of Agoo, in the province of La Union, where they stayed with my stepmother Antonina’s family – for the “duration” of the war.

My dad – with my stepmother Antonina and me in tow – made the long trip from our home in Baclaran, Parañaque (south of Manila) to Cubao (north of Manila) where my dad believed he would be safe for the “duration” of the war. My younger siblings – Hattie, Thomas, Roscoe, and Emma – were sent to the town of Agoo, in the province of La Union, where they stayed with my stepmother Antonina’s family – for the “duration” of the war.

To shield my identity and protect my dad, I was enrolled at the Cubao Elementary School under the name Julian Velez. The school was about three miles from our home on Natib Road. I would walk to and from the school for classes and other school activities.

I was in the third grade (I was in the third grade at the American Central School on Taft Avenue in Manila when the war broke out). In school, we were assigned books in which pages that had the American flag or any images or text relating to the United States or to America were pasted over with blank sheets of paper to conceal their content (curiosity, of course, led most of us to take peaks into the hidden text or pictures). We were taught Japanese – and did calisthenics daily while singing a song that started with “Odoro asahi no . . .”

On one of our school days, a short man wearing the uniform of the Japanese Imperial Army came to our classroom. Speaking in fluent English, the officer spoke about his role in the community. He must have given his name and rank, or wrote them down on the blackboard, but I didn’t notice. At the time, I considered his appearance a distraction.

Several days later, during a recess, the Japanese officer sought me out at the school yard. He told me he had something to tell me and took me to one side of the school building, away from the other kids.

Several days later, during a recess, the Japanese officer sought me out at the school yard. He told me he had something to tell me and took me to one side of the school building, away from the other kids.

“I lived most of my life in America,” the Japanese officer said. “And I went to college at Yale University,” he added. He then pulled out a wallet from which he showed me a picture of his “girlfriend” who he said was in America. I remember saying “really” and “how nice” but not much more.

About a week later, during a class recess, my Japanese officer friend came to the school yard looking for me, and when he found me, handed me a bag of Japanese food that he asked me to take home. I ate most of the food while I walked home that afternoon and discarded the bag in a ditch on Arayat Street.

About two months later, again during a class recess, my Japanese officer friend sought me out at the school yard. He took me aside – out of hearing distance from other kids. He sat on a bench while I stood in front of him. He held a twig which he used to gesture, and, looking me in the eye, told me he was going on a mission “tonight” to “kill an American.” I felt uneasy and concerned. He used the twig to sketch on the ground the location of the American’s “hiding place,” explaining that the “hiding place” was on Natib Road, off Arayat Street. As he spoke those words, I began to panic. I realized it was my sister Rosie’s house that he identified. Without saying a word, I turned away from him and started running home as fast as I could.

My Japanese officer friend came after me, calling out to me and yelling for me to stop – but I kept running until I lost him.

I got home scared and screaming. The first person I met at home was my sister Rosie. I yelled to her, half-crazed and excited, “sister, sister – the Japanese are coming – they’re going kill dad!” My sister Rosie grabbed me by my shoulders and, shaking me, told me to calm down. I explained to everyone who had surrounded me by then – my nephews Rafael, Frankie, and niece Teresita – what the Japanese officer had said to me at school.

I got home scared and screaming. The first person I met at home was my sister Rosie. I yelled to her, half-crazed and excited, “sister, sister – the Japanese are coming – they’re going kill dad!” My sister Rosie grabbed me by my shoulders and, shaking me, told me to calm down. I explained to everyone who had surrounded me by then – my nephews Rafael, Frankie, and niece Teresita – what the Japanese officer had said to me at school.

Sister Rosie’s husband, Joseph, and his two sons Rafael and Frankie, took my dad out of the house through the back yard and into the corn fields on their way somewhere I never got to know. That very same night we heard there was some Japanese military activity around the area where we lived – but no Japanese soldiers came to our house.

My dad returned to the house two days later. My dad never spoke to me about the incident or asked me any questions about it.

I did not attend classes for the next two school days – I would walk out of the house dressed for school, but would just walk around town and hang out at the rotunda until it was time to return home. On the third day, I decided that I would go to school. My classmates asked me questions, but I dismissed them all. I was hoping the Japanese officer would not ever again come to the school.

But he did. The Japanese officer came over to the school yard while we were in recess. I tried to avoid him, but he picked me out and took me aside. I was nervous and worried. And then he spoke.

“I know your father is American. But I would not hurt him.” He said that he only wanted me to know that he knew.

I said nothing. I don’t think I even looked at him while he spoke the words.

I felt relieved when he turned and walked away.

I kept silent about what happened at the school when I got home that afternoon. As in the last two days, when I was asked if I had seen the Japanese officer again, I said no – and not much more.

I did not return to Cubao Elementary for the following school year, in 1943. The war had intensified.

And I never got to see my Japanese Imperial Army officer friend again.

I will forever remember my Japanese Imperial Army officer friend whose name or rank I regret to not know. I often wonder what his fate was after the war. I have a feeling that he survived the war – and that he remembers a little odd-looking boy he met in the Philippines whose father was an American hiding from the enemy.

——————————————

——————————————

FOOTNOTES:

- My sister Rosie was my dad’s daughter from his first wife, Demetria Osorio. My dad and Demetria had three children: Rosalia (sister Rosie), Vicenta, and Elena. After Demetria’s death in 1930, my dad married my mother, Soledad Ramos, with whom he had three kids: myself, Thomas Henry, and Hattie Florence. After my mother died in 1936, my dad married Antonina Ventura, with whom he likewise had three children: Roscoe Konklin, Emma Jane, and Walker Ernest. At seven years of age, I had nephews who were adults (children of my sisters Rosie, Vicenta, and Elena).

- My sister Rosie’s house was on #15 Natib Road. Sister Rosie and her husband Joseph Thomas Casey Jr. owned land on both sides of Natib Road. On the west side (#15 Natib Road) sister Rosie raised poultry (duck, turkey, and chicken), planted crop (corn, sugar cane, and pineapple), and had a handful of fruit trees. Across the street from the house, my sister Rosie had a piggery – about 50 pigs in a row of sties. Sister Rosie stopped farming when the Japanese military began to commandeer her produce (around the beginning of 1943); her piggery ran empty because Japanese soldiers would come over and take pigs away until they ran out. As their provisions were no longer arriving from Japan, the Japanese military began to commandeer all available food products from the population.

- Also on Natib Road (north of sister Rosie’s house) was the home of a family of Swiss nationals with whom we had very little interface.

- North of the Swiss home on Natib Road was the home of the Paz family. Jaime “Jimmy” Paz was my friend and classmate at the Cubao Elementary School. Jimmy would scare the wits out of our teachers by drawing war planes with the American star on their wings. On weekends, Jimmy and I hung out at the huge Cubao rotunda. Jimmy later became an executive at the Development Bank of the Philippines.

- Also on Natib Road (next to my sister Rosie’s piggery) lived the family of a retired Spaniard whom my dad befriended. In some ways, the Spaniard protected my dad who passed himself off as Spanish (my dad had a decent Spanish vocabulary that helped).

- At the southernmost end of Natib Road lived the family of an American Air Force pilot (who perished at the start of the war) and his Japanese widow. They had three wonderful children who were all under the age of five in 1941.

- Sister Rosie’s husband, Joseph Thomas Casey Jr., owned a shoe store in Ermita, Manila; he shut down the store when war broke out. Joseph was also the chief of police of Quezon City. His position as chief of police protected us – the Japanese troops respected the huge sign on the gate to our home which read: “HOME OF CHIEF OF POLICE.” And my sister Rosie’s oldest son, Rafael, was a member of the Quezon City police force.

- Sister Rosie and her husband Joseph had five children: Rafael, Frankie, Joseph Jr., Teresita, and Dorothy – all of them my nephews and nieces. They called me Uncle Sunny. Dorothy – the youngest – and I were of the same age.

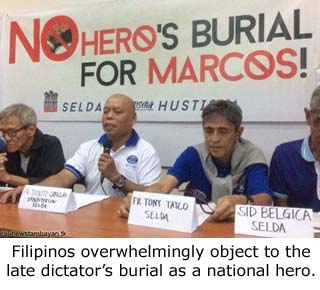

Three members of the Marcos family – Imelda Romualdez Marcos and her children Maria Imelda ‘Imee’ Marcos and Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos Jr. – refuse to admit that the name of their late husband and father, former dictator Ferdinand Edralin Marcos, is so irremediably tainted, discredited, and despised.

Three members of the Marcos family – Imelda Romualdez Marcos and her children Maria Imelda ‘Imee’ Marcos and Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos Jr. – refuse to admit that the name of their late husband and father, former dictator Ferdinand Edralin Marcos, is so irremediably tainted, discredited, and despised. The three continue their fight to gain control of the Philippine government in an effort to accomplish the late dictator’s dream of establishing a Marcos royalty and change the name of the country to ‘Maharlika.’ The steps they hope will help achieve their goal are: (1) have the late dictator proclaimed a ‘national hero’ and belatedly interred at the Libingan Ng Mga Bayani (Heroes’ Cemetery), and (2) win the country’s presidency. Through the presidency, the three hope to set up a new dictatorship and – eventually – a Marcos royalty, and then rename the country. It’s what the late dictator wished.

The three continue their fight to gain control of the Philippine government in an effort to accomplish the late dictator’s dream of establishing a Marcos royalty and change the name of the country to ‘Maharlika.’ The steps they hope will help achieve their goal are: (1) have the late dictator proclaimed a ‘national hero’ and belatedly interred at the Libingan Ng Mga Bayani (Heroes’ Cemetery), and (2) win the country’s presidency. Through the presidency, the three hope to set up a new dictatorship and – eventually – a Marcos royalty, and then rename the country. It’s what the late dictator wished. Imelda, Imee, and Bongbong cling on to wealth said to have been plundered from the country’s treasury and deny and suppress the grievances of the more than 100,0001 citizens that were wrongfully imprisoned, tortured and displaced or murdered during the late dictator’s rule.

Imelda, Imee, and Bongbong cling on to wealth said to have been plundered from the country’s treasury and deny and suppress the grievances of the more than 100,0001 citizens that were wrongfully imprisoned, tortured and displaced or murdered during the late dictator’s rule. 1 Amnesty International (AI) reported that about 70,000 people were imprisoned, 34,000 tortured, and 3,240 killed during the Marcos dictatorship.

1 Amnesty International (AI) reported that about 70,000 people were imprisoned, 34,000 tortured, and 3,240 killed during the Marcos dictatorship.

The Japanese military controlled information published by local broadcast and print media – propagating lies about the war situation. For example, during American air raids, I would count between 100 and 200 US Air Force planes in the sky and watch them from a hillside dive-bomb and strafe the nearby Camp Murphy which was occupied by the Japanese air force. Very, very rarely would I witness an American plane shot down during a raid. Each morning following an air raid, however, the Manila Tribune would run a headline that would read: “200 YANK PLANES SHOT DOWN OVER LUZON.”

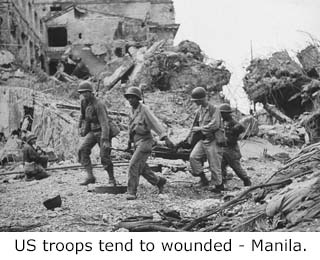

The Japanese military controlled information published by local broadcast and print media – propagating lies about the war situation. For example, during American air raids, I would count between 100 and 200 US Air Force planes in the sky and watch them from a hillside dive-bomb and strafe the nearby Camp Murphy which was occupied by the Japanese air force. Very, very rarely would I witness an American plane shot down during a raid. Each morning following an air raid, however, the Manila Tribune would run a headline that would read: “200 YANK PLANES SHOT DOWN OVER LUZON.” American forces started bombing vital Japanese bases and fortifications in the greater Manila area in September 1944. In the first week of February, 1945, rumors started spreading that American troops were coming into Quezon City from the north on their way to Manila at a time when I would be celebrating my twelfth birthday. A regiment of Japanese troops had fortified themselves at the Catholic nunnery and the water reservoir in Quezon City.

American forces started bombing vital Japanese bases and fortifications in the greater Manila area in September 1944. In the first week of February, 1945, rumors started spreading that American troops were coming into Quezon City from the north on their way to Manila at a time when I would be celebrating my twelfth birthday. A regiment of Japanese troops had fortified themselves at the Catholic nunnery and the water reservoir in Quezon City. The video accompanying this story shows 144 images of the death and destruction wrought by the liberation. Ninety-five percent of these images are credited to John Tewell who retired from the US Army and resided in Manila until his death. It was Mr. Tewell’s wish that these pictures be shared and propagated. Other pictures used in this video and story are official US Army photographs.

The video accompanying this story shows 144 images of the death and destruction wrought by the liberation. Ninety-five percent of these images are credited to John Tewell who retired from the US Army and resided in Manila until his death. It was Mr. Tewell’s wish that these pictures be shared and propagated. Other pictures used in this video and story are official US Army photographs.

In the city of Hayward, California, there was a school superintendent that the community’s civic and business leaders – as well as parents and school teachers and administrators – admired and respected for his work in ameliorating the quality of instruction and the academic achievements of the students.

In the city of Hayward, California, there was a school superintendent that the community’s civic and business leaders – as well as parents and school teachers and administrators – admired and respected for his work in ameliorating the quality of instruction and the academic achievements of the students. The school superintendent in this story is Stan ‘Data’ Dobbs – the fourth school superintendent that the Hayward Unified School District’s (HUSD) board of trustees has hired and fired since 2010, a span of a little over five years. Four school superintendents in five years must be a record of some sort.

The school superintendent in this story is Stan ‘Data’ Dobbs – the fourth school superintendent that the Hayward Unified School District’s (HUSD) board of trustees has hired and fired since 2010, a span of a little over five years. Four school superintendents in five years must be a record of some sort. On July 23, Dobbs filed a claim against the school district, alleging that the school board and its president, Lisa Brunner, violated his “statutory rights to privacy” and made “defamatory statements” against him during the board’s July 13 meeting where Dobbs was publicly accused of entering into contracts without the board’s approval and of “receiving gifts.” The claim seeks unspecified damages. If the claim is denied, Dobbs is expected to sue the school district.

On July 23, Dobbs filed a claim against the school district, alleging that the school board and its president, Lisa Brunner, violated his “statutory rights to privacy” and made “defamatory statements” against him during the board’s July 13 meeting where Dobbs was publicly accused of entering into contracts without the board’s approval and of “receiving gifts.” The claim seeks unspecified damages. If the claim is denied, Dobbs is expected to sue the school district.

The great majority of Filipinos continue to admire and show support for President Rodrigo Duterte in spite of the rising voice of discontent and dissatisfaction among the nation’s intelligentsia. The discontent and dissatisfaction are brought about by three – among many – of the president’s widely publicized recent bloopers.

The great majority of Filipinos continue to admire and show support for President Rodrigo Duterte in spite of the rising voice of discontent and dissatisfaction among the nation’s intelligentsia. The discontent and dissatisfaction are brought about by three – among many – of the president’s widely publicized recent bloopers. In televised remarks to army troops in Zamboanga del Sur on August 10 this year, the president related an incident in which his eyes caught the legs of his vice president, Leni Robredo. Duterte said that he admonished himself “. . . don’t do it!” and added “but I kept staring at her . . . she is beautiful.” The president told his audience, somewhat lewdly, that if he became “unlucky” while travelling and his vice president succeeded him to the presidency, “you would not be listening to her when she speaks but would just keep staring at her because she’s beautiful.”

In televised remarks to army troops in Zamboanga del Sur on August 10 this year, the president related an incident in which his eyes caught the legs of his vice president, Leni Robredo. Duterte said that he admonished himself “. . . don’t do it!” and added “but I kept staring at her . . . she is beautiful.” The president told his audience, somewhat lewdly, that if he became “unlucky” while travelling and his vice president succeeded him to the presidency, “you would not be listening to her when she speaks but would just keep staring at her because she’s beautiful.” Last August 5, while talking of the recent visit of U. S. Secretary of State John Kerry to the Philippines and about U. S. Ambassador to the Philippines Philip Goldberg, Duterte told an audience of soldiers in Cebu City: “Secretary Kerry is okay, but his ambassador – that homosexual son of a whore – he gets my goat.”

Last August 5, while talking of the recent visit of U. S. Secretary of State John Kerry to the Philippines and about U. S. Ambassador to the Philippines Philip Goldberg, Duterte told an audience of soldiers in Cebu City: “Secretary Kerry is okay, but his ambassador – that homosexual son of a whore – he gets my goat.” Duterte has publicly announced the names or identities of what he said were drug pushers and drug lords with the admonition that police and other authorities were free to “kill” those of them that do not “voluntarily surrender.” In less than two months – as of August 9 this year – 513 drug “suspects” have been reported killed by Philippine National Police “for resisting arrest.” Human rights organizations have placed that number at more than 900, with some of the killings described as “execution style.”

Duterte has publicly announced the names or identities of what he said were drug pushers and drug lords with the admonition that police and other authorities were free to “kill” those of them that do not “voluntarily surrender.” In less than two months – as of August 9 this year – 513 drug “suspects” have been reported killed by Philippine National Police “for resisting arrest.” Human rights organizations have placed that number at more than 900, with some of the killings described as “execution style.”

The 2016 presidential primaries are history, and the 2016 Republican and Democratic conventions are over. These events have given the American people an insight into the two parties and their candidates. On November 8, Americans will decide who will lead their country for the next four years: Donald John Trump or Hillary Rodham Clinton.

The 2016 presidential primaries are history, and the 2016 Republican and Democratic conventions are over. These events have given the American people an insight into the two parties and their candidates. On November 8, Americans will decide who will lead their country for the next four years: Donald John Trump or Hillary Rodham Clinton. (1) Republicans are in utter disunity, Democrats are united. Ted Cruz refused to endorse Trump, while party leaders George H. W. Bush, George W. Bush, John McCain, and Mitt Romney, among others, indicated their disdain for Trump and boycotted the party convention. Democrats were united and unanimous in proclaiming Hillary Clinton as their presidential candidate.

(1) Republicans are in utter disunity, Democrats are united. Ted Cruz refused to endorse Trump, while party leaders George H. W. Bush, George W. Bush, John McCain, and Mitt Romney, among others, indicated their disdain for Trump and boycotted the party convention. Democrats were united and unanimous in proclaiming Hillary Clinton as their presidential candidate. While Donald Trump pictures America as a “broken” country and proclaimed that he “alone can fix it,” Hillary Clinton speaks about work “we are all engaged in” to keep America a great nation and which aims to “make our country even greater.” And while Donald Trump pitches a message of hatred and division, Hillary Clinton talks of her struggle for national unity and dialogue.

While Donald Trump pictures America as a “broken” country and proclaimed that he “alone can fix it,” Hillary Clinton speaks about work “we are all engaged in” to keep America a great nation and which aims to “make our country even greater.” And while Donald Trump pitches a message of hatred and division, Hillary Clinton talks of her struggle for national unity and dialogue.

Cronyism and the ubiquitous padrino (patronage) system describe an economy in which certain business people and government officials maintain a close relationship, resulting in favoritism in the allocation of government contracts, permits, grants, benefits, etc. In its more despicable form, cronyism makes use of illegal and corrupt practices, causing people to lose respect for, and develop a mistrust of, both business and government.

Cronyism and the ubiquitous padrino (patronage) system describe an economy in which certain business people and government officials maintain a close relationship, resulting in favoritism in the allocation of government contracts, permits, grants, benefits, etc. In its more despicable form, cronyism makes use of illegal and corrupt practices, causing people to lose respect for, and develop a mistrust of, both business and government. Every area of business in the Philippine economy is fueled by cronyism, including retail, manufacturing, banking, transportation, energy and natural resources, real estate and construction, and communications – and all branches and agencies of the government are affected.

Every area of business in the Philippine economy is fueled by cronyism, including retail, manufacturing, banking, transportation, energy and natural resources, real estate and construction, and communications – and all branches and agencies of the government are affected.

Filipinos whose marriages are utter failures can seek recourse through a marriage annulment, a decree obtainable from the church or a civil court under very limited and highly improbable or difficult-to-prove grounds. The process for a legal annulment is long and tortuous, and a great majority of Filipinos could not afford the time or the cost of a church-sanctioned or civil court-promulgated marriage annulment.

Filipinos whose marriages are utter failures can seek recourse through a marriage annulment, a decree obtainable from the church or a civil court under very limited and highly improbable or difficult-to-prove grounds. The process for a legal annulment is long and tortuous, and a great majority of Filipinos could not afford the time or the cost of a church-sanctioned or civil court-promulgated marriage annulment. But relief is in sight. Representative Edsel Lagman of Albay province has filed a bill – House Bill 116 – that seeks to allow absolute divorce in the country. The congressman says the bill would provide “a merciful liberation of the hapless wife from a long-dead marriage.” Rep. Lagman was the principal author of the country’s newly-enacted Reproductive Health Law which the Roman Catholic Church of the Philippines opposed with all its might.

But relief is in sight. Representative Edsel Lagman of Albay province has filed a bill – House Bill 116 – that seeks to allow absolute divorce in the country. The congressman says the bill would provide “a merciful liberation of the hapless wife from a long-dead marriage.” Rep. Lagman was the principal author of the country’s newly-enacted Reproductive Health Law which the Roman Catholic Church of the Philippines opposed with all its might.

Metropolitan Manila is made up of sixteen cities and municipalities. The region covers an area of 611 square kilometers (236 sq. miles) with a population of 12 million people. Metro Manila is likely the world’s most populated region, with a density of 19,000 persons per square kilometer (50,000 persons per square mile).

Metropolitan Manila is made up of sixteen cities and municipalities. The region covers an area of 611 square kilometers (236 sq. miles) with a population of 12 million people. Metro Manila is likely the world’s most populated region, with a density of 19,000 persons per square kilometer (50,000 persons per square mile). According to the Philippine Statistics Authority, 2.5 million vehicles of all types were registered to operate in the Metro Manila area in 2015 – more than 25% of the total number of vehicles operating in the entire country. On the other hand, there are only 1,030 kilometers of roadways in the entire region of 611 square kilometers.

According to the Philippine Statistics Authority, 2.5 million vehicles of all types were registered to operate in the Metro Manila area in 2015 – more than 25% of the total number of vehicles operating in the entire country. On the other hand, there are only 1,030 kilometers of roadways in the entire region of 611 square kilometers.

When he steps down from the vice presidency at the end of June this year, Jojo Binay will have to face reality: multiple charges for plunder, graft, and corruption will be filed against him at the Sandiganbayan by the country’s Ombudsman. Plunder – under Philippine law – is a nonbailable offense.

When he steps down from the vice presidency at the end of June this year, Jojo Binay will have to face reality: multiple charges for plunder, graft, and corruption will be filed against him at the Sandiganbayan by the country’s Ombudsman. Plunder – under Philippine law – is a nonbailable offense.